Teng & Perkins: Retro Rating & Asset Premiums

Study Strategy¶

Checklist¶

- Know the basics of retrospectively rated insurance (the features and benefits)

- Know how to calculate the premium for a retrospectively rated policy

- Be able to calculate the PDLD ratios

- Rating parameter method

- Empirical method

- Be able to calculate CPDLD ratios

- Be able to calculate future expected premium

- Be able to calculate the premium asset

- Be able to explain the basics of Fitzgibbon’s method

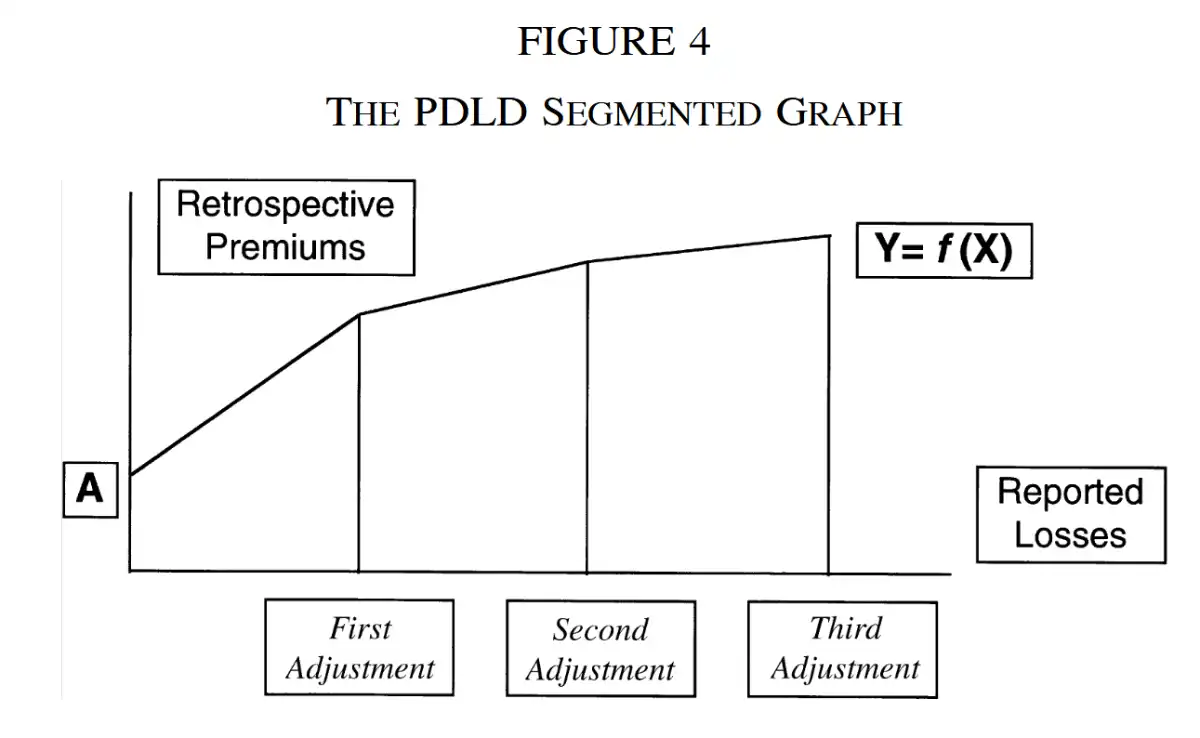

- Be able to recognize and explain the graphs of both Fitzgibbon’s method and the PDLD method

- Know the advantages and disadvantages of both Fitzgibbon’s method and the PDLD method

My Notes¶

- Retro adjustments

- First at 18 months of losses (+9 lag = 27 months of booked premium)

- Subsequent +12 to both (refer to table below)

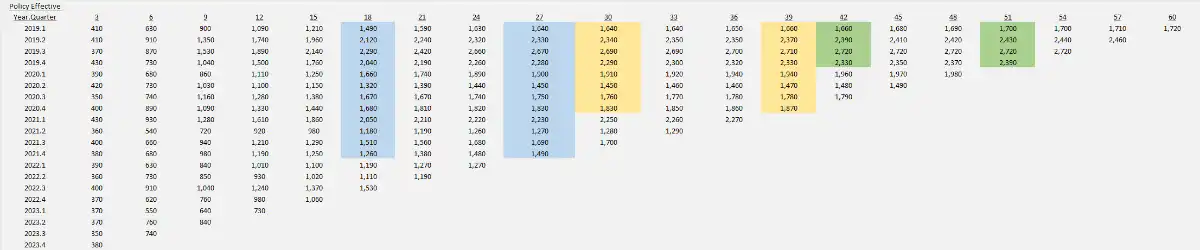

| Retro adj. | Losses a/o | Booked Prem a/o | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 months | 27 months | Blue |

| 2 | 30 months | 39 months | Yellow |

| 3 | 42 months | 51 months | Green |

| 4 | 56 months | Not yet reflected | N/A |

Note that in our calculations, the retro premiums should have reflected in the book. Thus we don't consider 18 month losses from 2022.2, 2022.3 & 2022.4 even though the retro adjustment has already been done. This is due to the lag.

Retrospectively Rated Insurance¶

After the policy expires → premium is set to reflect actual experience (premium adjusts up or down as losses develop)

- Features

- Even with no losses insured pays minimum premium

- There has to be a maximum premium (else no point of buying insurance)1

- There is a per accident loss limit that caps the amount of individual loss that can contribute to the additional premium being collected

- Benefits

- Good experience \(\implies\) Premium refunds.

- This purchase is attractive for insureds with good loss control and management procedures

- Insurer can attract good consumers this way

- Policyholders benefit by paying premiums gradually (instead of fully up-front). This way, they hold on to cash for longer \(\implies\) possible investment income.

- Insurer benefits → risk due to inflation, rate regulations, increasing claim frequency2, and lawsuits → shift to the insured \(\implies\) improves availability of insurance.

- Good experience \(\implies\) Premium refunds.

Retrospective Premium¶

- where

- \(CA:\) \(\text{Loss Conversion Factor}\times\text{Capped incurred Loss}\)

- to cover incurred losses (capped at per accident limit) and,

- expense → LAE (represented by \(C\), loss conversion factor), taxes (factor \(T\) multiplied to it) and other state assessments.

- \(b:\) basic premium includes \(= e - (C-1)E[A] + CI\)

- expense provision (company expenses)

- UW

- acquisition

- insurance charge (min and max)

- insured needs protection against large losses \(\implies\) max

- losses \(\gt\) max → insured benefits, insurer loses

- insurer needs to collect enough premium (cover expenses, bit of losses) \(\implies\) min

- losses \(\lt\) min → insurer gains, other loses

- IC \(=E(\text{Loss due to max}) - E(\text{Gain due to min})\)

- insured needs protection against large losses \(\implies\) max

- excess loss charge → accounting for risk of losses exceeding per-accident loss limit.

- expense provision (company expenses)

- \(CA:\) \(\text{Loss Conversion Factor}\times\text{Capped incurred Loss}\)

PDLD Ratio¶

Disclaimer

These methods are meant to be applied to an entire (or large segment of) book of business, rather than individual policies

Rating Parameter¶

| Rating Parameter | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| \(P_{n}\) | Premium at \(n\)-th retro adjustment | |

| \(BP\) | Basic premium | |

| \(SP\) | Standard Premium | |

| \(\dfrac{BP}{SP}\) | Basic Premium factor | |

| \(L_{n}\) | Total developed at \(n\)-th retro adjustment | |

| \(CL_{n}\) | Capped loss at \(n\)-th adjustment | Any loss contributing to additional premiums |

| \(LCR_{n}\) | \(\dfrac{CL_{n}}{L_{n}}\) = Loss capping ratio (% contributing to additional premium) | - \(\downarrow\) as data matures - If loss data already capped, \(L_{n} = CL_{n}\) and \(LCR_{n}=1\) - Otherwise, the ratio needs to be estimated - LCR = 0.9 \(\implies\) 1-0.9 = 10% of losses are eliminated by max, min and per |

| \(LCF\) | Loss Conversion Factor | loss-related expenses |

| \(TM\) | Tax Multiplier | premium taxes and other state assesments |

which is same as

Deriving this formula makes more sense, just remember the basic identities, and the fact that you have to break \(L_{n}\) and also use \(LCR_{n} = \dfrac{CL_{n}}{L_{n}}\).

There are two parts in this formula:

- \(\left(\dfrac{BP}{SP} \times \dfrac{TM}{ELR \times \%Loss_{1}}\right)\) → Charged even without loss, cost to write and service the policy (unrepeated in subsequent adjustments)

- \([LCR_{1} \times LCF \times TM]\) → cost of the policy for any reported losses (will be adjusted again)

And then,

-

For \(PDLD_{2} = \dfrac{P_{2}-P_{1}}{L_{2}-L_{1}}\)

- Eventually instead of \(LCR_{1}\) write the incremental Loss Capping Ratio, \(\dfrac{CL_{2}-CL_{1}}{L_{2} - L_{1}}\) in the (2) part

-

Pros:

- change to rating params can be accounted for (good for currently written policies)

- PDLDs are more stable than #Empirical method

- Cons

- rating parameters (LDF) cannot be average across segments (to avoid bias)

- thus have to retrospectively test PDLD ratios (actual vs expected)

- rating parameters (LDF) cannot be average across segments (to avoid bias)

Empirical¶

Don't use ultimate losses because future actual loss development will be accounted for in future premium adjustments.

- Aggregate by Policy effective Quarter3

- Say the first adjustment is done at 18 months, there is a lag in processing and recording adjusted premiums → for them to be booked it will take some more months after the adjustment has been made. (use Lag = 9 months unless stated otherwise)

- So we have to associate losses at 18 months with premiums booked at 27 months.

- Second adjustment is \(\text{Loss date 1} + 12\text{mo} = 30\text{ months}\) → 39 months premiums

- And so on… 42 months loss → 51 months premium, you get the point…

- Reasons for PDLD trending higher

- Perhaps rating parameters have changed (max or per accident-lim might have increased)

- Improvement in loss experience → larger portion of loss is within the cap \(\implies\) more "premium per dollar of loss"

CPDLD Ratios¶

Reminder

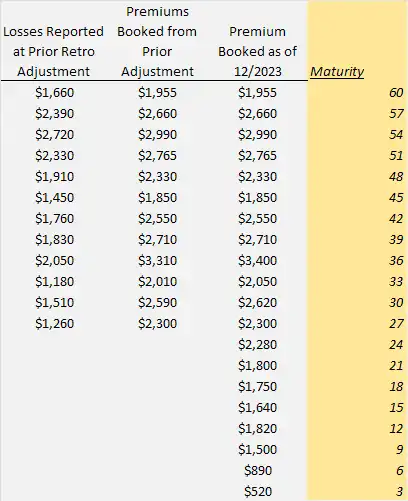

- What's the goal? → to estimate the premium asset

- Premium asset = \(\sum\text{future adjustments on E(Future losses)}\)

This is the weighted average of all the PDLD ratios weighed by the \(\text{\% reported}\), giving more importance to latest PDLD ratios.

- where \(N\) is the total number of retro adjustments to be made in the future.

Premium Asset Calculation¶

Tip: Understand the Axes

- Before getting into the calculations, understand the Policy effective triangle well

- For any PQ → The number of months actually show how many retro adjustments they would have had.

- It would make sense if you are not given the full triangle to create a column for maturity of each Policy effective quarter.

- Notice how at 27 months for premiums, first retro adjustment takes place

- The next at 27 months

- Calculate PDLD and #CPDLD Ratios

- \(E(\text{Future Loss}) =\text{Ult Loss} -\text{Loss a/o most recent retro adj.}\)

- % earned factor for the latest year → to account for the fact that policies aren't fully earned by the end of the year

- If not given, state "I assume that, % earned 100%"

- Most recent retro adj. = prior retro adjustment

- % earned factor for the latest year → to account for the fact that policies aren't fully earned by the end of the year

- \(E(\text{Future Prem}) =CPDLD \times\text{E(Future Losses)}\) ← Corresponding values

- Refer to the top to understand how to map them properly

- Ultimate premium = \(E(\text{Future Prem})+\text{Prem booked a/o most recent retro adj.}\)

- \(\text{Prem Asset} =\text{Ultimate Prem} -\text{Latest Val. Prem}\) ← which is the diagonal prem

Mind the difference between the booked premiums for the ultimate premium calculation

- (4) has a/o most recent retro adjustment

- (5) is what is yet to be adjusted → latest valuation date (diagonal)

Future Premium (step 3) can be calculated in another way¶

Use \(\downarrow\) formula to find \(P_{3}\), premium at third adjustment

Then find ultimate premium \(P_{ult}\)

And subtract the both: \(E(\text{Future Prem})= P_{ult}- P_{n}\)

Next¶

- Why not use development method on premiums? Why use PDLD?

- Ultimate incurred loss can be estimated more quickly than retro premiums can be obtained. We get a better estimate sooner.

- LOGICALLY, retro premiums depend on incurred losses → thus look at the connection between them, instead of just premiums

- PROs of PDLD

- Based on rating formula → explainable

- Emphasis on Premium sensitivity (in line with regulatory procedures)

- Adapts to changes in retro parameters (other methods get distorted)

- CON of PDLD

- Ratios are difficult to come by (as params vary by year, state and plan)

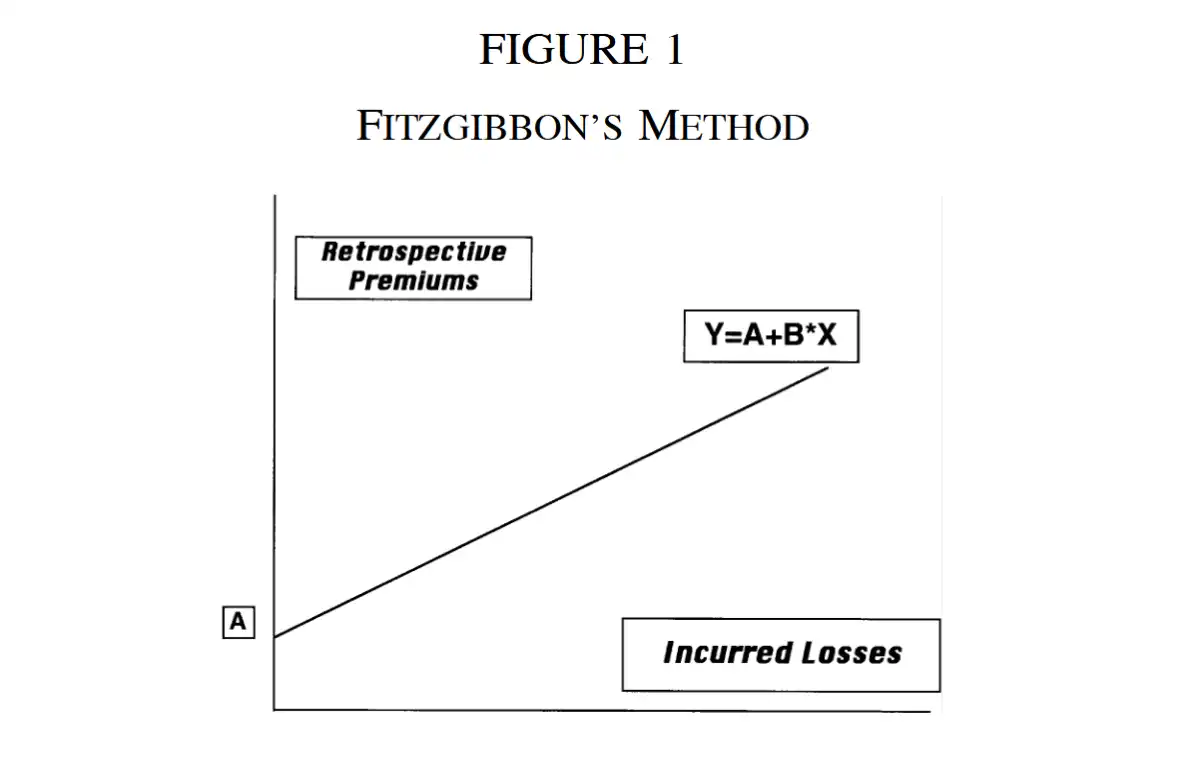

Fitzgibbon's method¶

To calculate premium asset, we use this reserve formula

- \(A\), \(B\) are estimated from historical regression

- \(A:\) intercept → minimum premium to cover expenses of writing and servicing policy

- \(B:\) slope represents the premium responsiveness

- SLR and Retro adjustments from mature PYs (old)

-

\(\implies\) We don't need to calculate plan parameters in the PDLD method

-

CON:

- Doesn't consider emerging loss experience.

- Won't adjust the premium for worse or better loss experience at each premium adjustment.

- Problem 2: SLR doesn't account for the composition of losses (can be one very large loss or multiple smaller losses)

- In contrast, for the PDLD method

- Premium responsiveness declines over time. Why? #later

Muffs¶

- Be careful when calculating CPDLD ratio… you must divide by the total weights (when finding for \(CPDLD_{2+}\), the \% reported don't add up to 1)