Lecture 54 Problems with Classical Game Theory I

The Challenge of Testing Classical GT¶

-

Empirical findings: systematic deviations between theoretical expectations and actual human behavior. Assumptions don't hold in practice:

- rationality

- strategic reasoning

- equilibrium selection

-

Why test? To understand how real people behave in strategic situations (vs Econs)

- bounded rationality

- social preferences

- framing effects

- assurance

- resentment

- reciprocity

Enter Behavioral Game Theory.

| Classical prediction | Empirical evidence |

|---|---|

| Players solve by iteratively deleting dominant strategies | Able to engage only a few steps of iterative dominance (higher is rare) |

| Assume that players and the belief that opponents are rational | Are they? |

Suppose \(j\) steps of iterated deletion of dominated strategies.

- \(j=1\), predictions of GT hold

- \(j=2\), majority violate

- Possibility: people have lesser confidence in the rationality of others to engage in IDDS. But there's two problems:

1. If P1 is rational, why does he believe P2 is not?

2. If P2 is believed to be irrational in simple games, then paapam (hardly any games exist where notion of rationality comes)

Suppose a game, 100 people pick a number between 0 to 100. The average of the numbers will be taken, the person with the number closest to 2/3 of the average will be considered winner.

- If everyone picks 100, then the winning number would be 67, no rational player would pick more than 67… but then everyone is rational

- So everyone picks 67… 44…33… all the way down to zero

- NE is zero (0).

But players chose 22 to 33… as they assumed others will not iterate more than 2-3 steps… or didn't play NE strategy even if they know it.

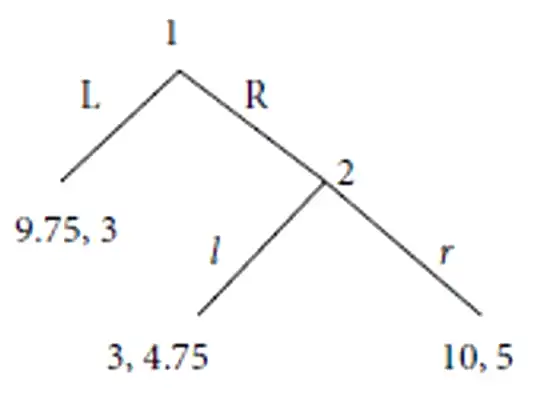

Failure of Two Steps of Iterated Dominance¶

- P1 lacks confidence in the rationality of the opponent and thus would select the \(L\) even though (R,r) would be the NE strategy.

- \(p= 0.97\) (that P2 will play \(r\) if P1 played \(R\))

- But experiment showed \(q = 0.83 \lt 0.97\)

- Thus, the P1 (66%) cannot be called irrational.

There are doubts about mutual rationality.

A Dynamic Game of Perfect Information¶

- P1 proposes a split of $5.

- If accepted by P2, game ends

- If rejected… the pie size shrinks to $2.

- P2 proposes a split of $2

- If accepted by P1, game ends

-

If rejected… no one gets anything.

-

NE split:

- P1 keeps $3, and P2 gets $2

- Experiments showed:

- P2 kept $2.83 (close to $3) and P2 got $2.17 (thus they accept it)

- But when pie shrank from $5 to $0.5

- P2 kept $3.38 (much lower than $4.5)

- not rational!

Framing Effects¶

- Normal form: 43\% chose R while extensive form 92\% chose R

Extensive form are frames which makes the dominant strategies more explicit

- Cognitively easier for players to spot dominated strategies.

- Visual structure illustrates sequential moves.

- Only 16% of P1 and 26% of PE chose equilibrium sequence with 3-steps reasons.

- Most player chose the safest (avoiding more steps)

- Games presented through verbal descriptions also altered player's ability to reason through.

Problems¶

- Players may possess "other-regarding preferences" (relative payoff instead of absolute payoff)

- P2 reject offers perceived as unfair even at a personal cost